When Victoria Gardens (now Rani Baug) was constructed as a botanical backyard within the 1860s, in then Bombay, it was a big colonial mission. The goal: to import vegetation from Asia, Africa and the Americas for cataloguing. “Its function [was to serve] as a laboratory for the Empire, and a Victorian English backyard construction was imposed on the Indian panorama to mirror a Eurocentric view,” says Amba Sayal-Bennett.

However colonial botany additionally concerned rigorous processes of extraction, switch and erasure — on this case extraction of vegetation and labour, switch of specimens throughout the globe, and erasure of native information. For the London-based British-Indian artist’s first solo present in India, titled Dispersive Acts at TARQ, she created a sequence of sculptures and drawings “fascinated by this botanical backyard as a colonial archive, a witness, and a web site of resistance”.

Amba Sayal-Bennett

The present is an element of a bigger physique of labor exhibited throughout Mumbai, London and New York that’s knowledgeable by her analysis into imperial gardens and colonial botany. Similtaneously Dispersive Acts, in London, Sayal-Bennett is a part of a gaggle present, Between Fingers and Steel, on the Palmer Gallery, and an exhibition referred to as Seeded Futures, Arboreal Drifts at Diana in New York. She was within the varied threads that related “this physique of labor throughout the three cities”.

A microcosm of the empire

Rani Baug, Sayal-Bennett says, has architectural components that join it to Kew Gardens in London, and “the Palmer area has historic hyperlinks to the India Rubber Firm”. In New York, she explores “the motion of stolen rubber seeds” from South America to India, by way of Kew Gardens.

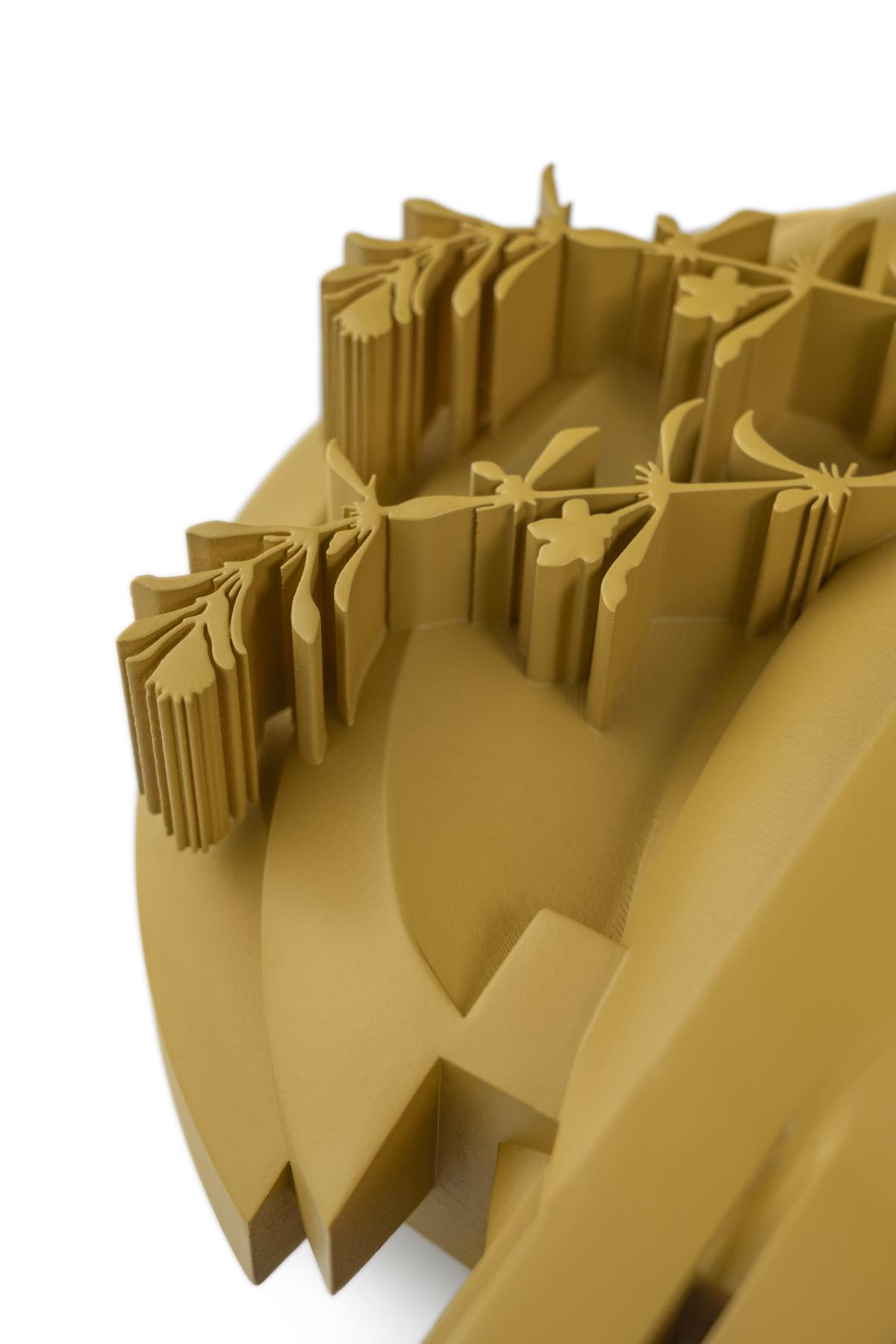

Seed Coat, 2024 (SLA, Resin)

“Rubber’s usefulness led to its switch and proliferation,” says Sayal-Bennett. “By 1873, its value had outstripped that of silver, and provides have been at a premium. A report commissioned by the India workplace beneficial that Britain generate and keep its personal shares by taking the high-yielding species Hevea Brasiliensis from South America to develop as a crop in plantations in India. Commissioned by the British authorities, in 1876, [British explorer] Henry Wickham stole 70,000 rubber seeds from Brazil, which have been introduced again to Kew Gardens earlier than their deployment to the colonies, together with India. In these contexts, I’ve been fascinated by how colonisation and cultivation are entangled by means of the imposition of sure crops or vegetation.” The botanical backyard in Rani Baug, she believes, could be seen as a type of microcosm of the empire with vegetation from all over the world, and within the case of rubber manufacturing, the imposition of a monoculture, erasing native vegetation and landscapes.

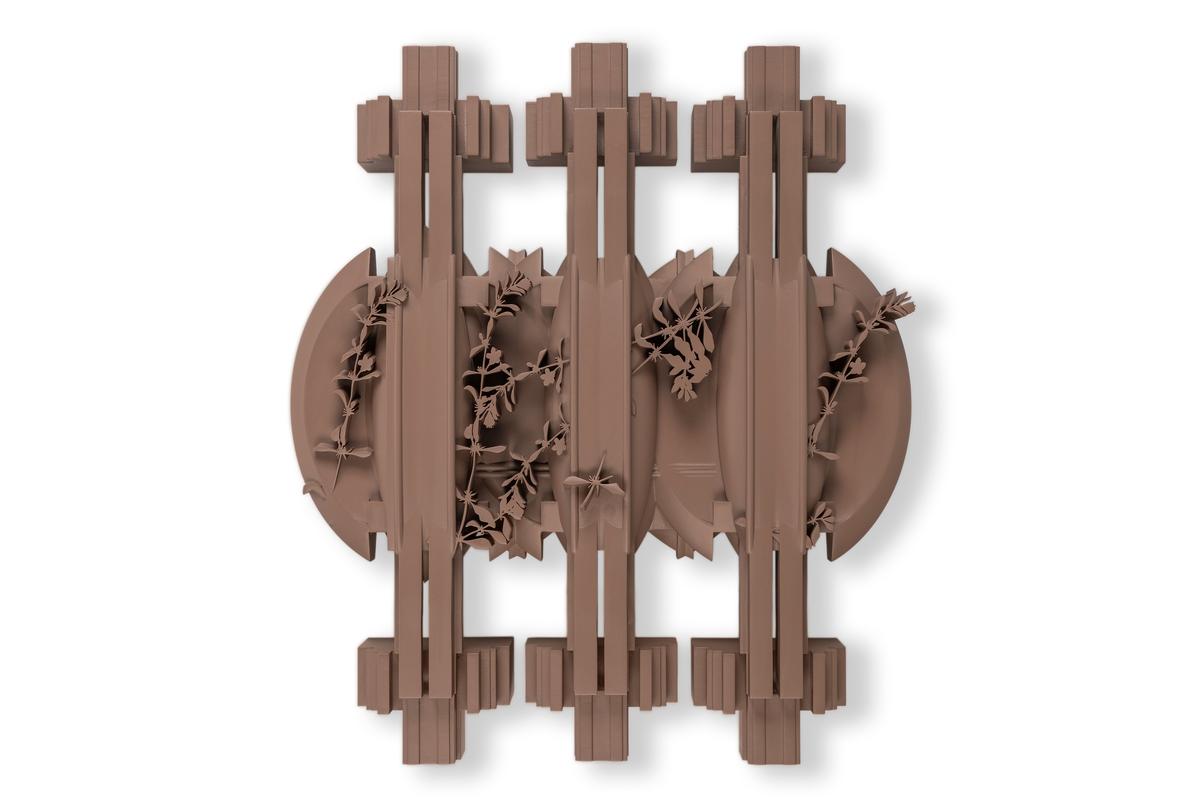

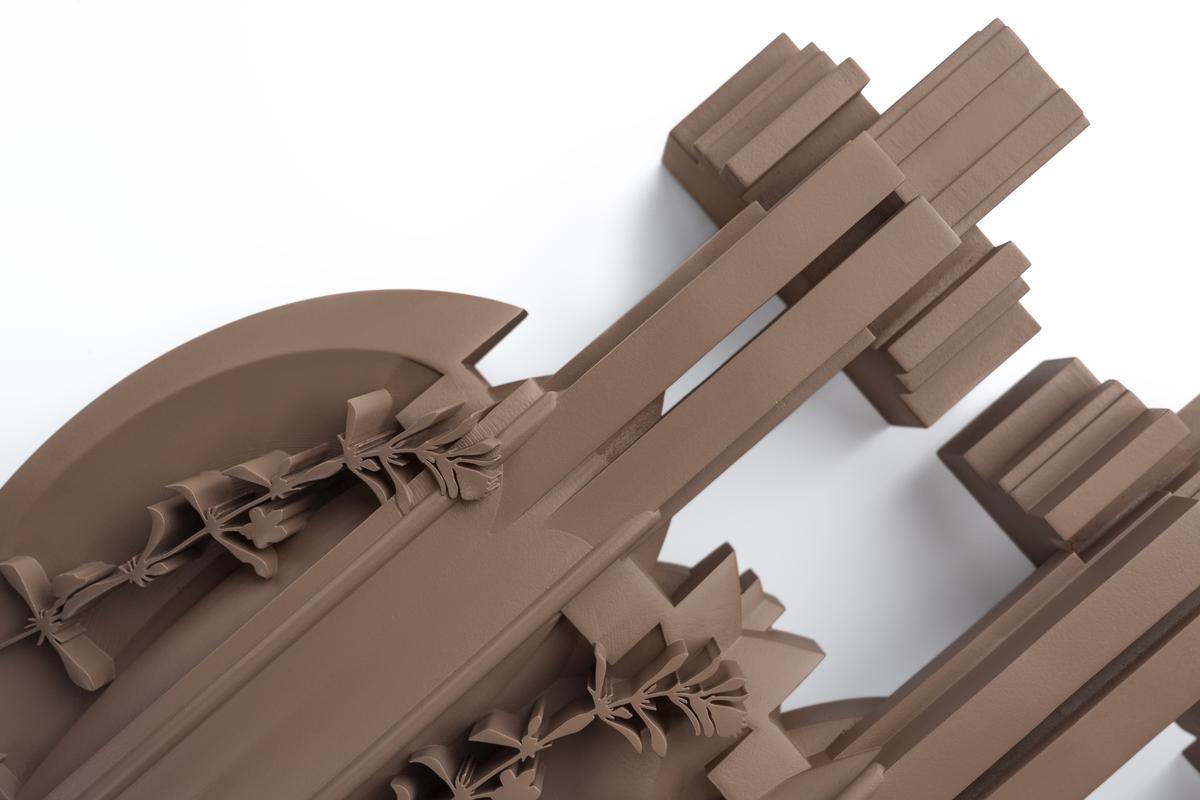

An in depth-up of Axil

Whereas researching the mission, Sayal-Bennett got here throughout writings by Judy Willcocks and Kieran Mahon on botanical drawings, which highlighted how illustrations have been a key element in monetising vegetation. “In these drawings, vegetation have been typically proven in isolation from any wider habitat on a clean background, encouraging the European scientific group to watch them for potential financial exploitation relatively than as a part of a symbiotic ecosystem,” she says, including, “The rubber seeds taken from South America to India didn’t take root. The setting rendered the seeds ineffective. Right here, the Indian local weather and soil fashioned an rebel infrastructure, a non-human company that refused to conform, refused for use, refused to help this imposed crop.”

Tiller, 2024 (SLA, Resin)

Leaning into her diasporic roots

The theme of “displacement and its inherited reminiscences and traumas” — as mirrored within the practices of colonial botany, the place vegetation are extracted from their indigenous context and relocated to new environments — has one more element. That of Sayal-Bennett’s late grandmother who was displaced from Punjab to the U.Okay. throughout the Partition. The artist shares that her id as a British-Indian and being a part of the South Asian diaspora in London has sensitised her to the genealogies of dispersion. “I all the time like listening to the associations folks need to this work, with many emotions each acquainted but troublesome to put,” she says. “There’s all the time a simultaneous situation of connection and estrangement that’s distinctly inherent to a diasporic expertise.”

Artwork Deco and resistance

At TARQ, artwork deco-style components discover a place throughout a number of of Sayal-Bennett’s works. “Mumbai is a metropolis with the second largest assortment of artwork deco buildings on the earth. I used to be fascinated about how this model could be seen as an announcement of independence; a mode chosen by Indian architects that was distinct from colonial influences, symbolising a transfer in the direction of a self-determined future,” she states.

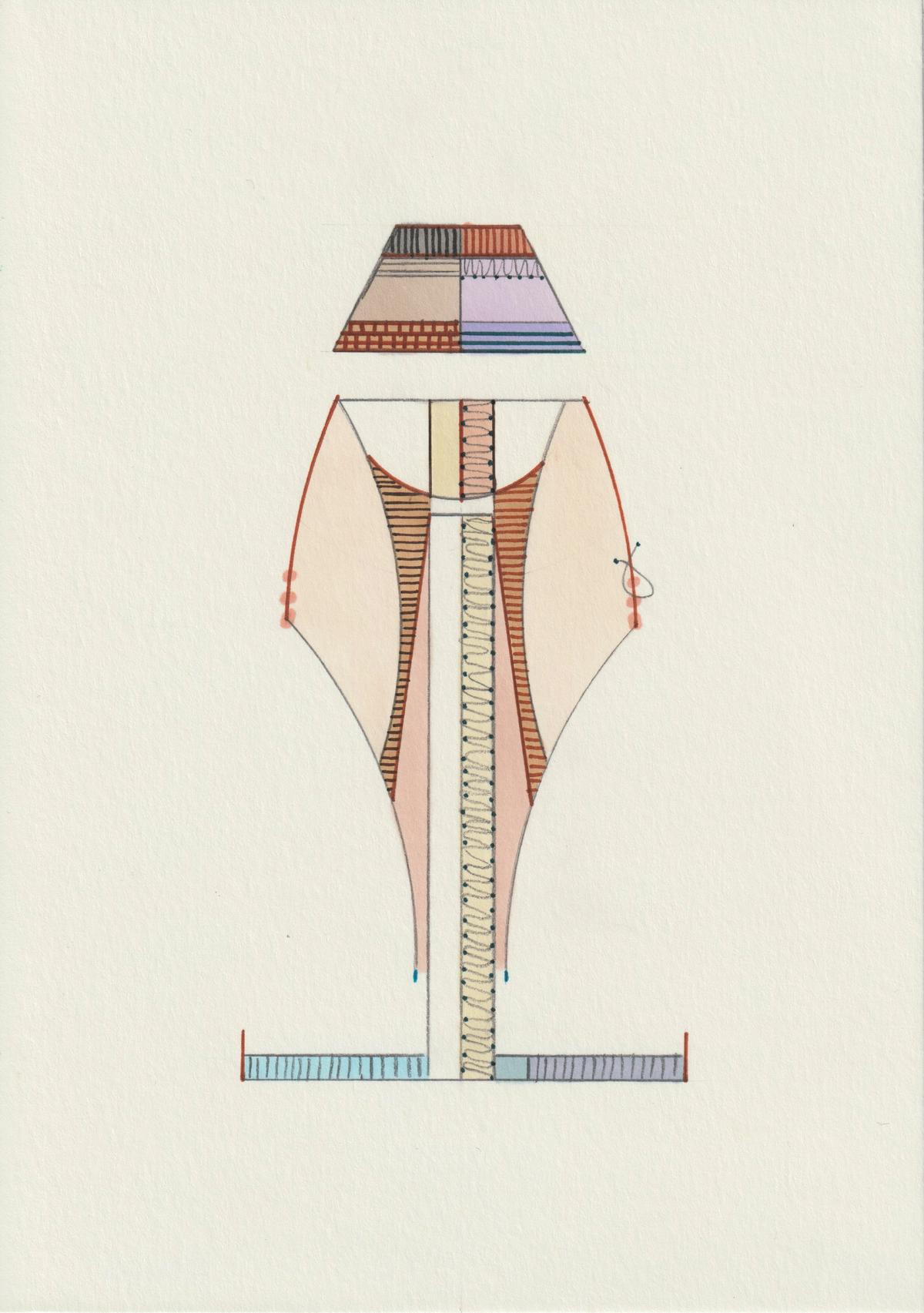

Morph, 2024 (ink, pro-marker and graphite on paper)

A piece titled Ziggurat, for example, reimagines the triumphal arch at Rani Baug’s entrance — put in in 1868 to sign a gateway to an arboreal paradise — in an artwork deco model. It additionally incorporates a porcupine flower from the Royal Albert Memorial Museum’s assortment, one other component that’s seen throughout completely different works. “The drawing is by an unknown Indian artist and was commissioned by the East India firm someplace between the late 18th and mid-Nineteenth century. Eager to use and export invaluable pure commodities, the corporate got down to document the wildlife of India,” she notes. “Indian artists have been commissioned to create detailed illustrations, however their names have been hardly ever recorded. These artists developed their very own model of portray, mixing Indian and European traditions, which got here to be often called the Firm Faculty model. I’ve been drawn to this hybrid model, which concerned a departure from the traces of typical European apply.”

Until September 21 at TARQ, Mumbai.

The author and artistic guide relies in Mumbai.

Printed – September 12, 2024 12:22 pm IST