To make theatre that was genuine to its cultural milieu and historical past whereas additionally being completely fashionable, each in content material and kind — this was Habib Tanvir’s life’s achievement. His theatre was exuberant, festive, celebratory, humorous, transferring, considerate and reflective. It was progressive and secular, and since it was created by a person with a Muslim title, it was reviled and attacked by Hindutva forces. He labored with rural actors to create performs that appealed to audiences far past the agricultural. Within the historical past of Indian theatre, Habib Tanvir was a singular presence.

Born in Raipur in 1923, he went to Bombay to pursue a profession in movies within the mid-Forties. However the decisive affect on him on the time was his entry into the Indian Individuals’s Theatre Affiliation (IPTA), the place he met and befriended artistes equivalent to Balraj Sahni, Dina Gandhi (later Pathak), Zohra Segal, and M.S. Sathyu. The left-wing perspective of IPTA was to stick with him all through his life, although he cast his personal distinctive path in theatre.

A scene from Habib Tanvir’s Agra Baazar staged at ‘Habib Utsav’ in Bhopal on November 21, 2009.

| Photograph Credit score:

A.M. Faruqui

The movie trade disillusioned him. It worshipped cash, not artwork. He got here to Delhi, the place he joined Hindustani Theatre, the place he met Moneeka Misra, a theatre director skilled within the U.S. They fell in love and bought married.

In 1954, Habib Tanvir wrote and directed his first masterpiece, Agra Bazaar, on the life and artwork of the plebeian Nineteenth-century poet Nazir Akbarabadi. It was an astonishing manufacturing, for 2 causes. One, the protagonist Nazir by no means seems within the play — as a result of no biographical details about him was obtainable, at the same time as a big corpus of his poetry had survived, handed on orally from technology to technology. Two, Habib Tanvir requested residents of Okhla village on the outskirts of Delhi to behave within the play — his first try to make theatre with rural folks.

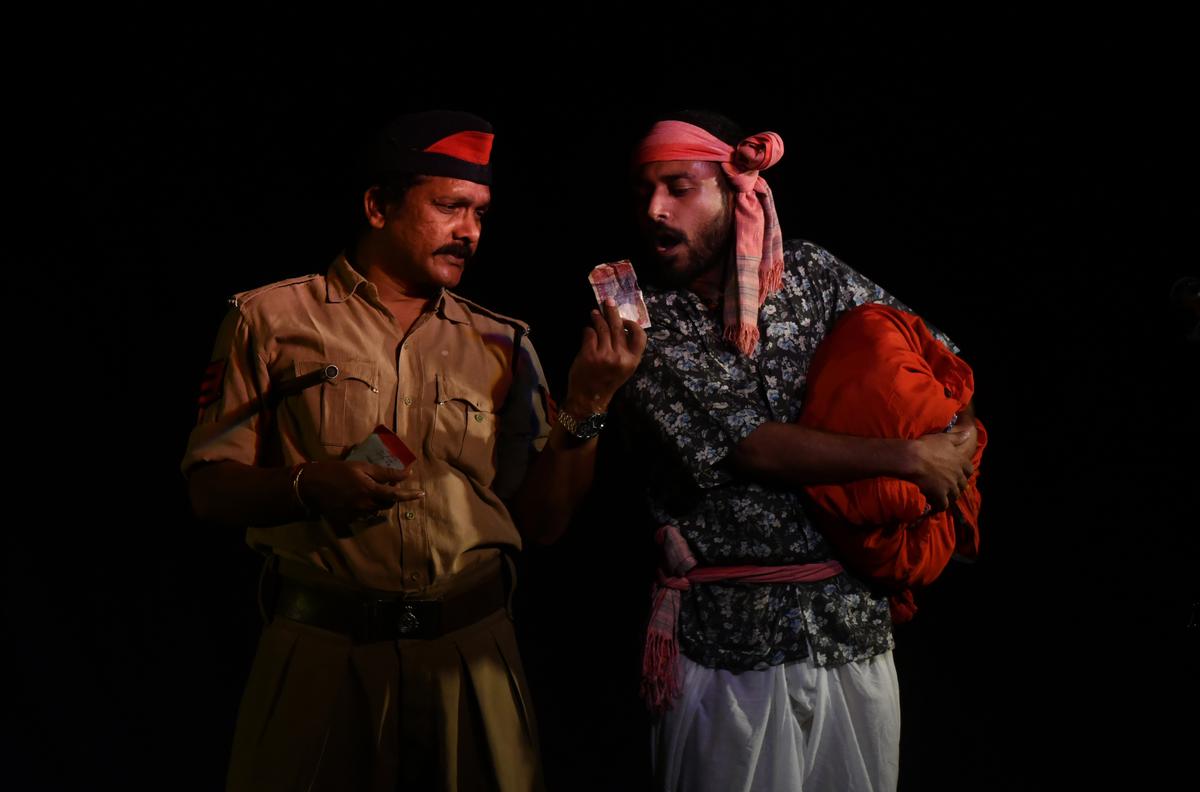

From Charandas Chor by Naya Theatre. Staged in December, 2019 as a curtain- raiser to the primary state convention of Community of Creative Theatre Activists Kerala (Natak) in Ernakulam.

| Photograph Credit score:

Thulasi Kakkat

A scene from Habib Tanvir’s play Mrichchakatika.

| Photograph Credit score:

The Hindu Archives

Quickly after, he left for Britain to get formally skilled as a director, on the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts (RADA), and the Previous Vic. He was in his thirties, with over a decade of theatre work below his belt. What he learnt in Britain, most of all, was what he wanted to reject — the overly regimented theatre of the time, real looking in a photographic kind of method, about middle-class life. He longed for the free-flowing, pleasant, irreverent theatre that he had loved as a baby in Chhattisgarh. He returned to India and got down to discover rural actors.

Watch | Sudhanva Deshpande remembers legendary theatre character Habib Tanvir

The primary lot of six rural actors he picked got here with him to Delhi in 1958. They have been all kind of unlettered, however masters of the Nacha, the agricultural theatre of Chhattisgarh. They acted and danced with abandon, sang melodiously of their open, robust voices, have been masters of farce, and will additionally transfer you to tears. With them, and with Moneeka as his companion, he based his personal firm, Naya Theatre, in 1959. They produced play after play, touring the nation extensively, however whereas his performs of the time had spark, actual success eluded him.

Habib Tanvir watching a play rehearsal.

| Photograph Credit score:

Sudhanva Deshpande

It was befuddling. Why have been these nice actors, who have been so pleasant once they carried out within the villages, so stiff and inflexible on the city stage, he puzzled. It took him 15 years, from 1958 to 1973, to determine it out. He was forcing them to talk in Hindustani, a language that was alien to them, and he was ‘directing’ them, telling them the place and find out how to stand, the place and when to maneuver, what gestures to make use of. When he melded collectively three rural farces right into a single play in Gaon ke naon sasural mor naon damad (‘I’m the son-in-law and my in-laws’ home is my village), he requested his actors to talk in Chhattisgarhi and improvise their strikes.

It was magic. With their tongues and our bodies unshackled, the actors have been magnificent. Remarkably, city audiences, most of whom had no familiarity with Chhattisgarhi, embraced the play. A string of hits adopted, many recognised as masterpieces of contemporary Indian theatre — Charandas Chor (Charan the thief), Mitti Ki Gaadi (Sudraka’s The little clay cart), Bahadur Kalarin, Shajapur Ki Shantibai (Bertolt Brecht’s Good individual of szechwan), Hirma ki amar kahani (The immortal story of Hirma), and Kamdev ka apna, basant ritu ka sapna (Shakespeare’s A midsummer evening’s dream).

Habib Tanvir, an artiste-activist, he was dedicated to the values of secularism and social justice.

| Photograph Credit score:

Particular Association

Habib Tanvir was a formidable mental with deep insights in regards to the Natyashastra and Indian performing traditions, a classy aesthete who soaked up influences from all around the world, and a citizen-activist dedicated to values of secularism and social justice.

“In India, the economically poorest are the culturally richest, and the economically richest are the culturally poorest,” he would typically say. He devoted his life and his artwork to uplift the tradition, and the voice, of India’s poorest. And he did it with unparalleled verve, magnificence, and pleasure.

Sudhanva Deshpande is an actor, director, and organiser with Jana Natya Manch and Editor with LeftWord Books. He has co-directed two documentary movies on Habib Tanvir and is the writer of Halla Bol: The Dying and Lifetime of Safdar Hashmi.

Session at Literature pageant

Sudhanva Deshpande’s session at The Hindu Lit Fest, 2024 is titled ‘Recalling Habib Tanvir: Excerpts from the movie and a chat’. Will probably be held on January 26, 3.15 p.m. at Sir Mutha Live performance Corridor, Harrington Highway, Chetpet, Chennai.